I was fully prepared to five-star Irish Wish before I watched it. This checks all my boxes in concept: It’s sort of a holiday-themed Netflix romcom starring Lindsay Lohan. I love Falling for Christmas (2021). I don’t currently have St. Paddy’s Day movies on rotation, but I was willing to start a pile.

Irish Wish features Lohan’s character wishing she were marrying her long-time crush while she’s in Ireland for his wedding. Thanks to magic, she swaps places with the bride (a friend of hers). Of course, this is a whole monkey’s paw affair, where it turns out what she wants isn’t what she needs. The changed circumstances highlight to Lohan that she’s not meant to be with the crush. It also helps her realize she’s in love with the guy who played Jack Crusher on Picard.

The milieu establishes that love is a soul mates affair, and I like soul mates in a fantasy setting. Crush and Friend manage to fall in love again despite the situation-swap. And when Lohan manages to undo her wish, she still ends up with Jack Crusher. They were always meant to be. Aww.

Lohan is perfect in this. Even better than Falling for Christmas! (Which came from the same creative team, too.)

This is as good as any Netflix romcom, with all the usual asterisks added and then dismissed. You don’t eat Kraft dinner and complain it didn’t taste like filet mignon.

There have also been a lot of monarchist nonsense in Netflix romcoms, and those tend to be my less-favorite. Fantasies of wealth (and the accompanying security) are a staple of the romcom genre in general. I don’t begrudge anyone their fantasies of security, but I appreciate when a romance makes it easier to swallow by taking us far, far away from real-life politics. Give me Aldovia instead of England, please. (Letterboxd)

Irish Wish did not distance itself from real imperial politics.

The wealthy crush’s family lives in Killruddery House (Wikipedia), an English-occupier house in Elizabethan style. The only filming location necessary to Ireland is the Cliffs of Moher, a famous tourist destination, which feels like a very shallow scoop off the top of Irish-themed things. And Lohan’s tricky little wish isn’t manipulated from one of the many potential local Irish spirits, but Saint Brigid. (Wikipedia)

The mere inclusion of Brigid explicitly in her saint form is one markedly post-Christian reformation. In an attempt to be fair, I’ll note that an overwhelming percentage of modern Irish people identify as Catholic. 94.1% of Irish identified as Catholics in a 1961 census; even in the 2022 census, 69% continue to identify as Catholic. I tripped across these numbers reading a nuanced essay about Brigid as a historical saint, pre-Christian goddess(es), and as a title on Stone, Soil, and Soul. (It’s a substantial and worthy read.)

Paganism isn’t just history in Ireland; as with most indigenous cultures, contemporary peoples continue to observe their traditions. (Psyche) The colonial presence of the British still hasn’t been accepted either. A united Republic of Ireland continues to be a hot topic, and the party in favor for election this year would pursue it. (NPR)

Hence Irish Wish calls itself Irish, but it’s a specific Ireland: a colonized, Catholic Ireland, where Lindsay Lohan’s crush is a selfish manipulative Irish-accented occupier whose family wealth comes from conquering and her Happily Ever After comes with the much-cooler English hero. Why is the romantic couple American and English in a movie with “Irish” in the title? Kind of a letdown, y’all.

It’s a reminder of the deeply conservative nature at the heart of Hallmark-style romcoms.

In this case, my Kraft dinner came tainted with a memory of my Irish grandma swearing about the English, and there was no way I could possibly enjoy it as much as Falling for Christmas.

So I guess this one isn’t starting off my St. Paddy’s Day-themed watch list. Considering St. Patrick was all about converting the Irish to Christianity (Time), I wasn’t married to it anyway, but I really like all the silly green decorations of the holiday, and I like having an excuse to slap Irish flags and cartoon leprechauns on everything. I’m not gonna say I’ll never revisit (Lindsay Lohan is so charming! she’s doing great y’all! I love to see it!) but I’m not keen on this approach at all. I’ll keep my fingers crossed for my grandma’s dream of an English-free Ireland though.

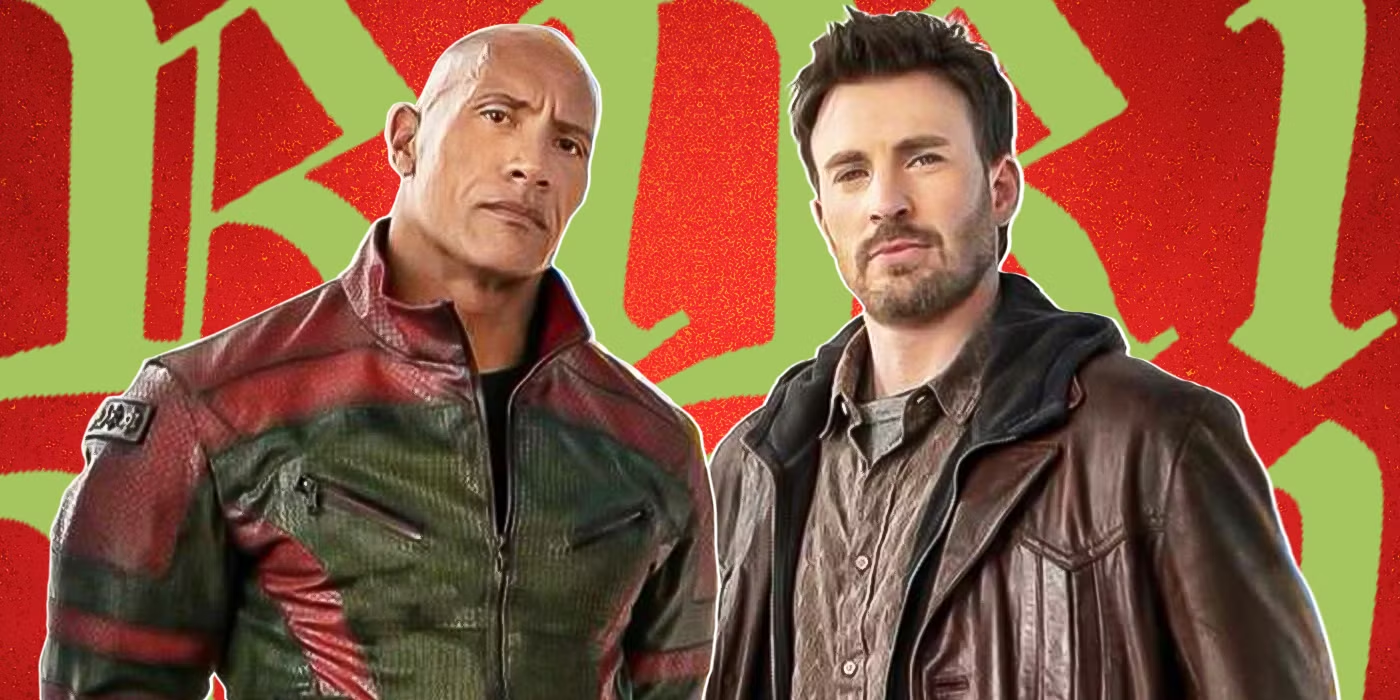

(image credit: Netflix)